instantiator.dev

tech, volunteers, public safety, collective intelligence, articles, tools, code and ideas

- Presence (tool) (in dev)

- ListSky (tool) (in dev)

- The Epistolorean (service)

- Consensus Games (service) (in dev)

- JSON to Smart CSV (tool)

- Escape the Review (profile)

- In this house... (calendar)

8-bit Supercomputer

articleIt took me 3 weeks to complete the day 11 puzzle for Advent of Code on a BBC Micro this year, and you’d be hard pressed to describe my solution as “proportionate” or “necessary”…

TLDR: I wrote an arithmetic library in BBC BASIC to work on arbitrary sized numbers, and containerised beebjit to run it at modern speeds. You’re welcome to plunder my solutions and use them in your own projects.

8-bit Supercomputer

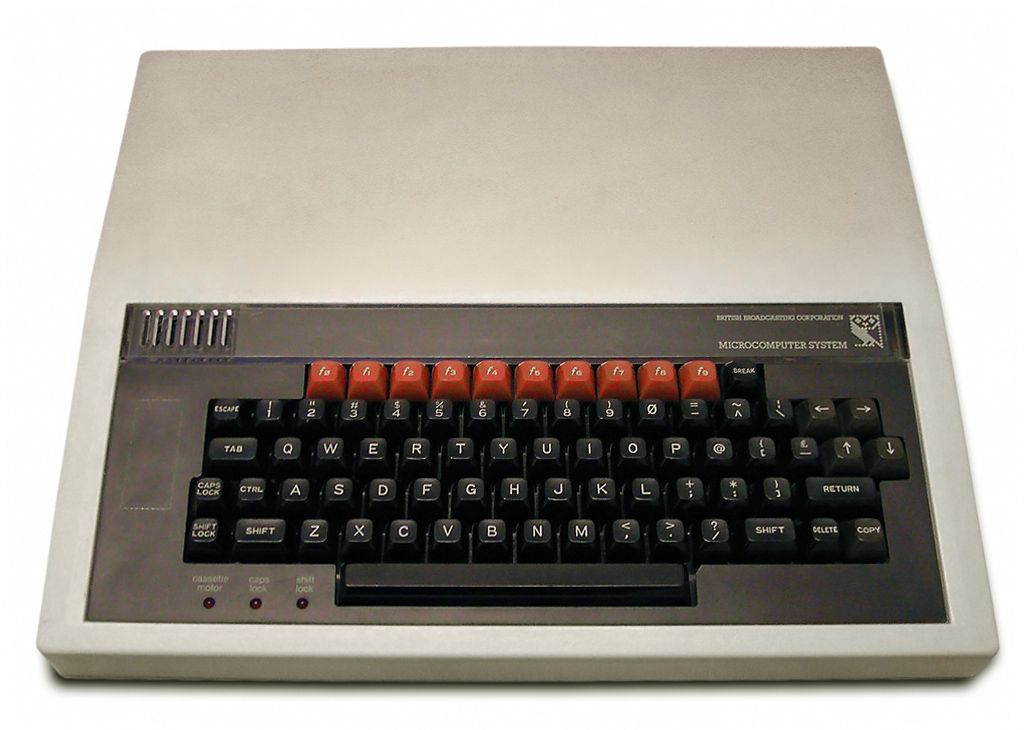

The BBC Micro is an iconic little computer from 1981, firmly printed into the minds of school-children in the UK who grew up in the 80s. (I feel a close kinship with it - as I’m from 1981, too.)

Advent of Code is a series of coding puzzles, published in December of each year, of (approximately) increasing difficulty. There are 2 puzzles per day for each day until Christmas.

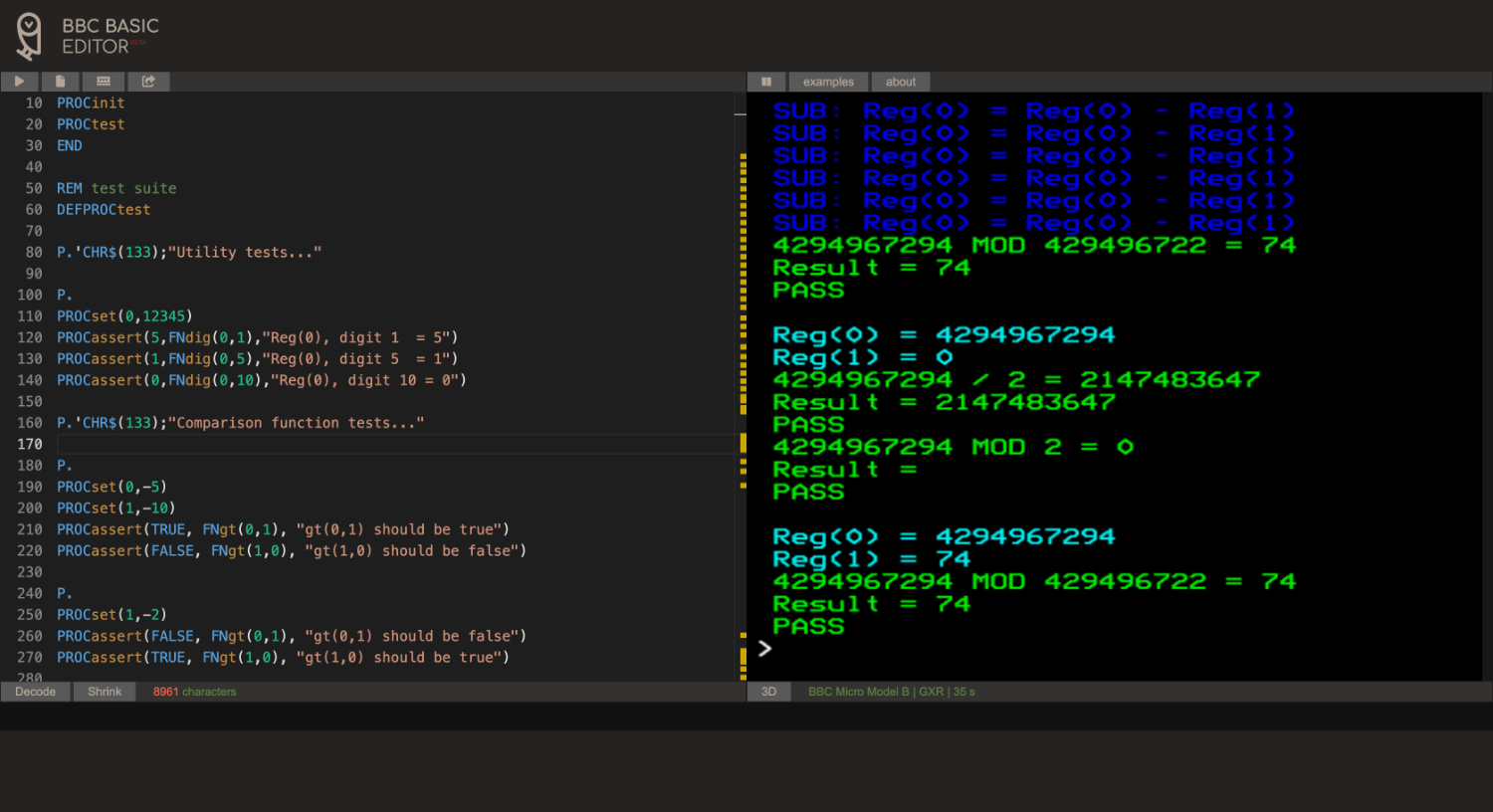

This year (2022), I decided to attempt the challenge in BBC BASIC - the programming language that shipped with the BBC Micro. There’s a fun editor and emulator at bbcmic.ro, and lots of fun examples of tiny programs written with it for the BBC Micro Bot.

Everything was going swimmingly until day 11 (although on occasion days I came perilously close to the memory limits of the BBC)… I completed the first part of the problem in reasonable time, but the second one had me stumped. There were 3 difficult aspects to it:

- It required a little bit of knowledge of remainder theorem.

- It required use of very big numbers (larger than can be represented with 32 bits).

- It required 10,000 iterations of a complex algorithm to reach the answer.

The poor little BBC Micro was not built to do this kind of work!

1. The remainder theorem thing

Aspect 1 caught me out at first, but once I’d grasped it, I was able to make progress:

if you have a very large number and you want to reduce it, but also need to preserve the remainder properties when divided by a collection of other numbers, get the product of those other numbers, divide the original by that, and take the remainder.

For example:

- You have a large number:

5000 5000 / 3 = 1666 r 25000 / 5 = 1000 r 05000 / 11 = 454 r 6- You can divide 5000 by (

3 x 5 x 11 = 165) to preserve the remainders, ie. 5000 / 165 = 30 r 50(take the remainder)50 / 3 = 16 r 2(the remainder is preserved)50 / 5 = 10 r 0(the remainder is preserved)50 / 11 = 4 r 6(the remainder is preserved)

Fine - I had that part of the problem solved, and for a while my solution seemed to work, although it was taking a very long time!

2. Very Big Numbers

At first, everything seemed to be working, but then disaster struck! Despite reducing each value by the product of the numbers found in the real problem (2 x 3 x 5 x 7 x 11 x 13 x 17 x 19 = 9699690), the values reached during the calculations were still far too large and the program crashed out…

BBC BASIC can handle 32-bit signed numbers. That gives a range of -2147483648 through to 2147483647. I had run into a limitation of the computer.

I needed a way to do arithmetic with numbers of any size. Remembering that I’d read something about big numbers in one of my brother’s old BBC Micro magazines, years ago, I started searching. Sadly, I couldn’t find any reference to it.

I kept searching… and I did come across a couple of interesting hits:

- The

bigint.bbclibrary that’s bundled with R. T. Russell’s BBC BASIC for SDL 2.0 - An article by David Tall, found in MICROMATH, Autumn 1985 edition: Arithmetic with large numbers

Unfortunately, the bigint.bbc library doesn’t really fit my need here: It assumes the availability of 64-bit integers - and this means it’s only really going to work for the more recent/modern editions of BBC BASIC, rather than the original from the 80s.

David Tall’s article, on the other hand, was very promising! It describes how to use some procedures and functions he’d developed to work on arbitrary numbers stored as strings. The code itself was almost certainly provided on a tape or disk that came with the magazine - but sadly that was not available.

David Tall is a Professor of Mathematical Thinking at Warwick University, and maintains a professional and personal website. I reached out to him to ask if he still had any of the missing code. In response, he was very encouraging - but invited me to develop my own solution, rather than handing over his 1985 work.

I’m pleased to say that I did! It took a while, it’s not my finest work, and I had to learn some basic pencil-and-paper arithmetic again to do it - but it works.

You can see the library here: bignum.v1.basic (and you’re more than welcome to plunder it for your own project, or improve on it!)

So I now had functions to parse numbers of indefinite size! (Well, limited by strings in BBC BASIC - which gives an upper limit of 255 characters. Still, that’s much bigger than before, and easily big enough for my purposes…)

A trick I picked up was to initialise strings to the maximum length on first use. If a string variable is replaced with a string that’s longer, the original becomes wasted space and the computer must claim additional memory (from a very limited supply!) By initialising each string at maximum length, the space can be reused.

3. 10,000 iterations

Everything was back on track - I could do my calculations without crashing the machine, but there was another problem. This solution is going to take a very long time to run! BBC BASIC is a fast implementation of BASIC (for which a lot of credit is attributed to Sophie Wilson’s work) - but it’s all running on a 6502 processor (clocked at ~2Mhz), and it’s an interpreted language.

Add to that the laboriously slow big number arithemtic library I’d just written and multiply the work to 10,000 iterations… We have a problem!

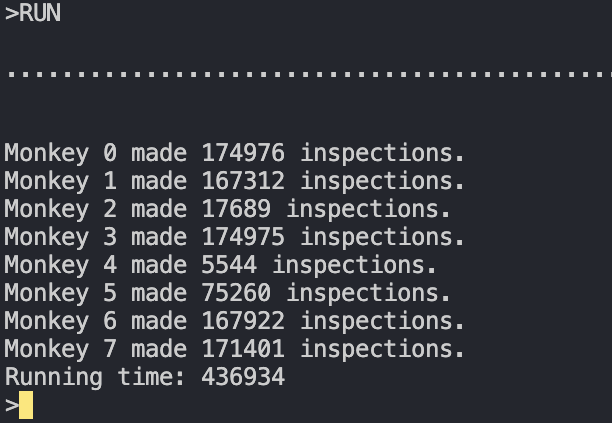

I’ll cut to the chase: The solution ought to complete in about 72 minutes on a standard BBC Micro model B. That’s far too long for me. Particularly when I didn’t know for sure that I had it right, yet!

I turned to the black art of “finding a fast emulator” - and beebjit by Chris Evans was just the ticket!

As the name implies, it’s features “just-in-time” compilation, which means it will compile the 6502 code it needs to run into host code, as it encounters it. This means the BASIC interpreter can now run at the speed of the modern super-fast computer you’re using.

This reduced my runtime to 13 minutes. It’s still quite long, but it’s good enough to iterate a few times and get the solution just right.

In the form found on github, beebjit is reasonably straightforward to compile for yourself - but I went ahead and containerised it with docker to make it a bit easier to use.

You can see my solution here: instantiator/advent-of-code-2022/beebjit

I was particularly interested in the fast terminal mode that it offers so that’s what my scripts will do. With docker installed on your system, you can:

- Run:

docker-build.shto create a docker image containing beebjit, compiled and ready to use. - Run:

run-fast-bbc-terminal.shto launch beebjit on the terminal in fast mode.

NB. It seems as if I/O is pretty slow for beebjit in this mode, but when it’s not printing to the screen it’s very fast!

Of mice and men

- Deep Thought ran for 7.5 million years, determining that the answer to the ultimate question of life, the universe and everything was 42.

- Earth was destroyed 5 minutes before it was due to finish calculating the original question, destroying 10 million years worth of work.

- beebjit running my solution took 13 minutes to determine that the level of monkey business on day 11 of Advent of Code 2022 was

30616425600.

A BBC Micro conducting arithmetic on arbitrary size numbers, at modern speeds, is an 8-bit super-computer in my books!

That’s good enough for me.