instantiator.dev

tech, volunteers, public safety, collective intelligence, articles, tools, code and ideas

- Presence (tool) (in dev)

- ListSky (tool) (in dev)

- The Epistolorean (service)

- Consensus Games (service) (in dev)

- JSON to Smart CSV (tool)

- Escape the Review (profile)

- In this house... (calendar)

3 excellent ways to build trust with your users

articleThis article was originally posted to Medium.

3 excellent ways to build trust with your users

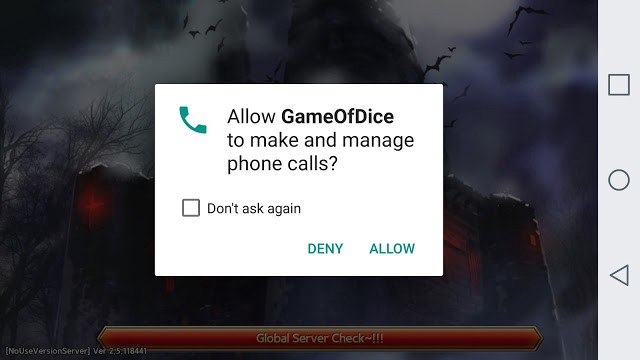

I don’t see why it needs that permission!

Android apps ask for unusual permissions sometimes, and they don’t always seem to make perfect sense.

This article assumes that you are already a trustworthy developer. If you are harvesting user details without consent or concealing other nefarious activity on a user’s device, please read up on fraud legislation (US | UK) and then make your way to the nearest police station.

The Android permissions system doesn’t know how to explain what it needs clearly, and some permissions lock away a group of features, when only one is needed.

For instance, this screengrab from a game demonstrates a fear response to a regularly requested permission. It was posted with this title:

Quickest way to get your app deleted

The app is asking for a permission called “make and manage phone calls”. When the poster attempts to find out more, he reports that “it went to a screen that said the reason that needed this type of access was to provide me with rewards and perks”. He didn’t believe it, because for him it didn’t seem plausible that those two things could be linked.

Is that a useful explanation? Almost certainly not. What’s really going on?

The phone’s unique identity (UDID) is locked away behind a specific permission. Being able to provide a unique identity for a player is important for developers. They need to know who is attempting to do what in their game, manage and maintain scores, save points, etc.

Many app developers use the phone’s UDID for this — and if they didn’t they would have to turn to alternative means to get a unique identity for the player. There’s an argument to say that UDID isn’t always the best choice — after all, it can lead to mistakes when there is more than one user per device. It is, however, one of the simplest choices for a developer, even if it leads to permissions dialogs that disrupt users, as illustrated above.

1. Only ask for what you need!

This is a simple one — whenever you ask for a permission, you are taxing your user with a decision. Sometimes you are asking for that permission is based on limited information about what you intend to do with it. Sometimes you are asking for it at a busy time when the user wishes to get some tasks done with your app, and sometimes you are asking for it at a time when the user would rather not be interrupted. Those are not mutually exclusive!

Another alternative to to the example above might have been to rely on a third party infrastructure to collect a syndicated identity (such as “Sign in with Facebook” or “Sign in with your Google account” or “Google Play Games”). Each of these have advantages — in that if all you need is an identity, then it is clear to the user what they are giving you.

However, the simplest example of all would be simply for the app to create and store a fresh GUID (also known as a UUID) when it is first opened, and then to use that GUID as the user’s identity.

A GUID looks like a jumble of 32 characters (really it’s a 128-bit integer), often separated by hyphens into easy-to-read blocks. GUIDs have the special property that a fresh one is guaranteed to be unique in the universe (not withstanding malicious behaviour) and staggeringly difficult (effectively impossible) to guess.

Every user has a compliance budget (a gentle alternative interpretation derived from Beautement, Sasse and Wonham’s paper: The Compliance Budget: Managing Security Behaviour in Organisations). Whenever you ask them to do something like this you eat into that budget. With apps, where installation and uninstallation is frictionless, you will find that consuming the whole budget can lead directly to lower retention and loss of interest from your users — so it makes good sense to assess each permission you need, and spend some effort deciding if you really need it (and if so, how you will explain that to the user).

Because of this, it becomes clear pretty quickly that quietly creating a GUID is the simplest way to identify a user, and it uses zero budget, as creating and using a GUID requires no permissions. If you need other user properties, of course, and you don’t want your users to have to type them all in then perhaps a syndicated identity (ie. Facebook or Google) is a better way to go.

2. Explain yourself clearly

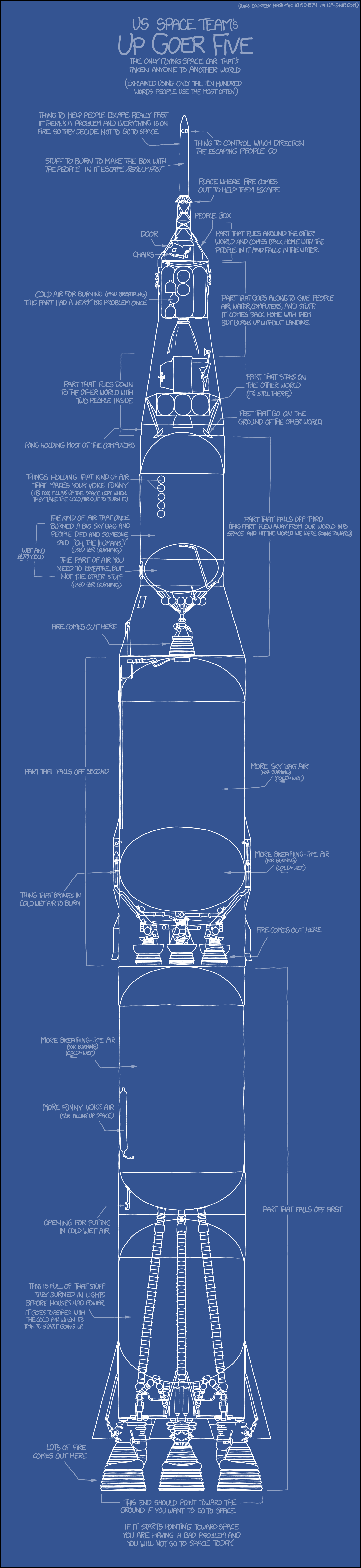

I recommend visiting the xkcd post Up-goer Five to see that blueprint in full.

There’s a subreddit called r/explainlikeimfive where users ask for explanations of complex real-world concepts in simple terms “like I’m five”. People crave this — and for good reason: Nobody can be an expert in everything, and very few of your users are experts in the Android permissions system! Hell, you aren’t and you’ve been developing for decades!

A good illustration is this post by u/brisdaz in subreddit r/AndroidQuestions asking about what seems to be a particularly scary permission for them.

It also has this scary permission description:

Device ID & call information. Allows the app to determine the phone number and device IDs, whether a call is active and the remote number connected by a call.

This is the second time we’ve seen an app trying to learn the device ID — and in both cases the user has responded with caution.

In my reply, I consider a few components of this puzzle, looking in detail at the various permissions. Each could have been explained clearly with a few short words:

- Device ID and call information. We’ve discussed this, it seems to be being used to help identify the device and so indicate which user is taking part in a particular poll. This is fine if it’s explained clearly, or perhaps it’s worth considering an alternative identification scheme, such as the Google Play Games API.

- Camera and storage. In this case, I couldn’t immediately find a use for this, although it turns out it’s used to read a QR code during the quiz, to help identify users that are all participating at the same venue. A good use, but perhaps it needed a little more explanation!

- Draw over other apps. Now here’s a tricky one! Apps like facebook messenger use this permission so they can create little bubble heads, and pop up notifications on the screen even when you are in another app. This particular permission could create a real security hazard though: a malicious app might decide to obscure and fake the interface of another, and force the user to perform actions they didn’t mean to do. It’s a permission that’s being tightened up by Android in version 8.0 (Oreo), so we should expect that the risks are going to be diminished by this — but at the same time, it’s really important to have a good reason to ask for this permission!

The onus for providing reasons why an app needs a particular permission really falls on the developer and designer. If a user refuses a particular permission, and it’s essential, the app should explain in simple terms exactly why it needs that permission.

It’s impressive that the developers of the Android permissions API foresaw this, and provided a utility method: shouldShowRequestPermissionRationale() to determine if you should go to the lengths of providing an explanation for the user.

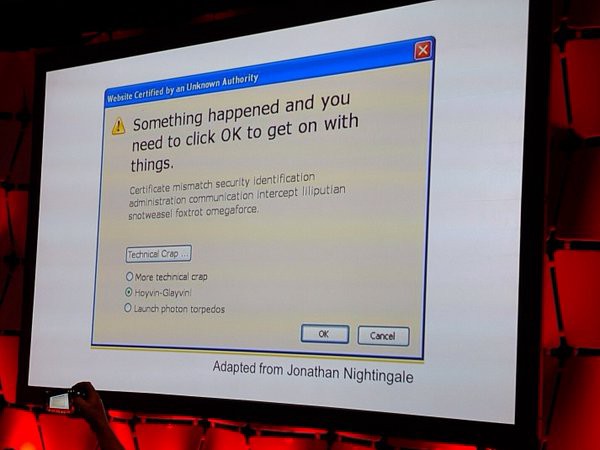

At current time, this method returns true if a user refuses to grant a specific permission. I’d argue that this method should always return true, although the counterargument to that is that if we swamp our users with text, they’ll simply learn not to read it — as we’ve seen with the classic example:

If you’re ever at a loss for words to describe a permission, first think hard about what you need it for. I’d also recommend referring to Gizmodo’s field-guide to what app permissions really mean, as an example of just how you can explain those permissions.

3. Engender trust by being open

In the example above, the developers of the app built it to accompany a quiz night in a pub, and are clearly open about their intentions. It seems unlikely that they would also be attempting to harvest and sell personal details of their users, and in fact it would be counterproductive to do so: Being caught would kill their main business, which relies on the trust of their pub-goers and quiz-entrants.

Having an open identity means putting yourself “out there”. This carries some, risk of course: You’re going to receive some abuse from people who don’t like your app. The benefit is that users can see you and learn about you. Open a twitter account, a facebook page, and a website, and link those back to real people. Each of these is evidence of the fact that you’re not likely to disappear overnight, as you’ve clearly invested time and effort and your self in the app’s online presence.

This also raises the bar for malicious developers. If doing this became normal, then bad actors would have to come up with fake identities that stand up to higher levels of scrutiny, and everything we can do to raise the bar makes it more expensive for bad actors to profit from crime.

Companies do this all the time. Pizza Express were established in 1965, and use that not only to show that they are experienced at serving pizzas, but that customers have trusted them reliably enough over all this time that they’re still in business.

I’d suggest you stop before prefixing your company name with the word “Honest”, though. It just never seems to engender the same level of trust if you have to explicitly state that you’re honest!